New Urbanism is dead. Long live New Urbanism.

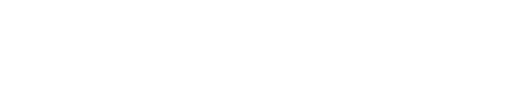

Seaside is the little town on the Northwest Florida Gulf Coast, a mile further west along the beach from where I have been fortunate enough to keep a home for the past couple of decades.

Designed and built in the 1980’s by visionary landowners, architects, and town planners it quickly became the poster child for New Urbanism. It got a further popularity boost when it was the ‘perfect town’ featured in the Jim Carrey movie, The Truman Show.

New Urbanism isn’t actually new.

For sons and daughters of the Wirral like me, we all learned about the origins of Port Sunlight and the remarkable foresight Lord Leverhulme displayed in understanding that building homes, amenities, and public spaces his workers enjoyed was good business.

If you haven’t been to Port Sunlight and wandered its perfectly manicured lawns, grand approaches to its Soap Factory, the Lady Lever Art Gallery, and the function rooms where The Beatles played their first gig, you really should.

But like so much innovation, a good idea in the UK becomes an industry in the US.

Seaside could probably link its idealistic heritage back to Port Sunlight. This small US coastal town features in the A Vision of Britain documentary narrated and produced by the then Prince of Wales, now King Charles III. Its architectural codes, community ideals and people-centricity undoubtedly helped shape the Monarch’s thinking in building his Poundbury town on his Duchy of Cornwall land.

Seaside’s 40-year existence holds some lessons for others to consider.

Beautiful as it is, kissing the white sand and turquoise waters of this coast, Seaside has its challenges. Despite the high ideals of neighbourliness, walkability, sustainable design and aesthetics – one factor has interrupted its progress – people.

Rather like those artist’s impressions of happy families pushing prams while toddlers run free across the open plaza at the foot of monstrous 1970’s tower blocks in Liverpool, Birmingham and Manchester, the reality is always a little different: people it seems just don’t perform the way planners, dreamers and architects hope for.

In the UK many of those high-rise towers have now been bulldozed less than 50 years after being built, hated by their residents, becoming lawless and hopeless estates.

In Seaside’s case the challenge has been the opposite – too much money.

Seaside marketed itself better than anyone, created the demand and in doing so cemented those original ideals of New Urbanism. That original plan was to build a new place, rooted in the smalltown Americana vernacular, where people would live a wonderful life.

The problem, if it is that, is it was too popular.

Only an hour’s flight or a 6-hour drive from some of America’s most successful cities – Atlanta, Nashville, Birmingham, Dallas and Houston – everyone wanted a piece of it.

With these ‘money rich, time poor’ suburbanites longing for a week at the beach – that is the vacation allocation the US work system affords even the highest paid executives – Seaside became a ‘must do’ destination.

Prices went up, supply was limited and only the very wealthy could afford it.

But, most importantly, these new homeowners weren’t actually living there. Cornish, North Welsh and Cumbrian readers will sympathise.

Though the design plan was to build proximity to your neighbours, to share cheery ‘hellos’, cups of coffee and glasses of wine on sunset porches, the reality is many of the properties are holiday homes, sat empty for much of the year, or rented out to families who come for a week, disappear, and are replaced by a facsimile family for the next 7 days.

The handful of year-round-residents huff and grumble about the renters and the homeowners who rent to them. Security guards patrol to enforce town rules about where bikes and golf carts are permitted to go and chase gaggles of visiting teenagers on and off the beach at nighttime.

This wasn’t part of the plan – everybody was supposed to love everyone not loathe them.

But when you can command upwards of $20,000 a week to rent out your Seaside second home, make more than $500,000 for a 36-week rental season, the motivation to own in Seaside changes. Humans are fickle like that, especially about money.

Don’t get me wrong, the town still looks pristine and still offers a fabulous vacation experience, but that wasn’t its purpose at the outset. It was meant to be somewhere to live not a resort. Perhaps building it in such a glamorous beachside spot was the mistake?

Back to Leverhulme.

In what seems like a previous life, I recall Leverhulme Estates wanting to build on the land they own in Wirral. Much of this land is green belt – virgin, verdant fields, only sullied by countless cows – strictly out of bounds for developers.

Leverhulme’s development arm submitted plans to build on the little bits of green belt which separate one town from the next, preserving their standalone identities. The local authorities refused to play ball, and the plans have been largely iced since.

But what if new plans took a page from the New Urbanism handbook? What if a new settlement was built on the acres of land available just minutes from the motorway junctions which dissect it?

And what if the founding principles of Leverhulme’s Port Sunlight and King Charles’ Poundbury were adopted with a sprinkle of the marketing glitter of Seaside?

Even today, Port Sunlight manages the homes and communal areas to a set of codes and expectations. Refurbishments, vital in many of the century old homes, must be done a certain way to preserve the whole place integrity, it still looks much like it did when it was built.

And to avoid Seaside’s wealthy enclave factor, Poundbury has a 35% affordable housing quota, not built as an afterthought on some muddy backwater, but folded into the high streets, park-side communities, sharing hallways and driveways with the million-pound properties also available.

Rental units exist in both places, but strict restrictions on short term renting and sub-letting too, helping to create and shape community life. These are new urbanist ideals.

I know many readers of this column are in the property, development, construction sectors, others are in local government. I can hear them cry that the economics of development don’t support such pie-in-the-sky ideas.

But according to all sources, the UK is deep in a housing crisis.

One which, arguably, was hastened and facilitated by the current model for development and has failed to provide the homes required.

Again, people probably got in the way of such idealistic nonsense as a home for everyone who needs one.

The feeding frenzy to sink your pension into property drove the disastrous buy-to-let boom and crash, and the complicity of some not particularly imaginative or committed planning departments lead to the proliferation of poorly built 2-bedroom boxes which scar many towns and cities today.

In some cases, the desire to make a profit – both private developers seeking cash and local authorities hungry for extra revenue – trumped everything else, inviting the unscrupulous in search of a quick buck.

Unlike any other industry, it appears consumers – residents – were never consulted or considered beyond the statutory.

Imagine if people were asked what they wanted in a home?

Almost no-one would talk about experimental design, futuristic looks or contemporary materials. Architects and designers might be disappointed, but developers and planners should take note.

People would choose homes with adequate space, security and amenity, pleasing on the eye and engendering a sense of place, here, now.

In fact, superstar developers, millionaire architects and humble town planners already know this – after all where do they live? Belgravia, The Georgian Quarter, leafy suburbs, seaside Victorian villas – classic houses built in a conventional style which they have been able to personalise and turn into a home.

So why not repeat the magic for the rest of us? Walls, doors, roofs. Private front gardens and space for kids to play. Just as people have demanded for centuries.

And sustainability – the buzz word – isn’t just about carbon footprint, it is about building for the long term, nothing is more sustainable than a development which stands for centuries.

As the community in Seaside grapples with its evolution from town to resort, we all need to understand what people want from their community, their homes, their neighbourhoods – now and in the future. And local authorities need to create the rules and circumstances to deliver this.

Clearly, Seasiders today want holiday homes not a full-time residence because that profit motivation is strong – neither they nor the planners are wrong, and while this was perhaps not the wishes of those early adopters back in the 1980’s – things do change. Other communities along the beach have learned and have outlawed short term rentals, changing their buyer/investor dynamic.

And while this is all well and good in a privileged beach town, aren’t the fundamentals true everywhere?

Run down parts of towns do gentrify and become desirable again, economic rejuvenation arrives with high streets and civic areas being refurbished, and nearly always it is because traditional homes and buildings are being refurbished and rejuvenated which drives the repopulation so intrinsic to the success of place making.

Marketing dollars are spent by local authorities, developers and others to promote place. Wirral is aggressively marketing itself as the #LeftBank, positioning itself as the hipper, cooler sibling of rowdy, shouty Liverpool — it has made huge strides in reconfiguring its outdated shopping and transport network, but now needs the homes people really want to live in.

Perhaps that’s the new urbanism solution: “Don’t over think it, just build what people want”.