It isn’t every day Communist politics in Glasgow and the opinion columnists of The New York Times find themselves in lock step.

But 50-years ago today, the NYT described the words of a Scottish trade unionist as “the greatest speech since Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg address”.

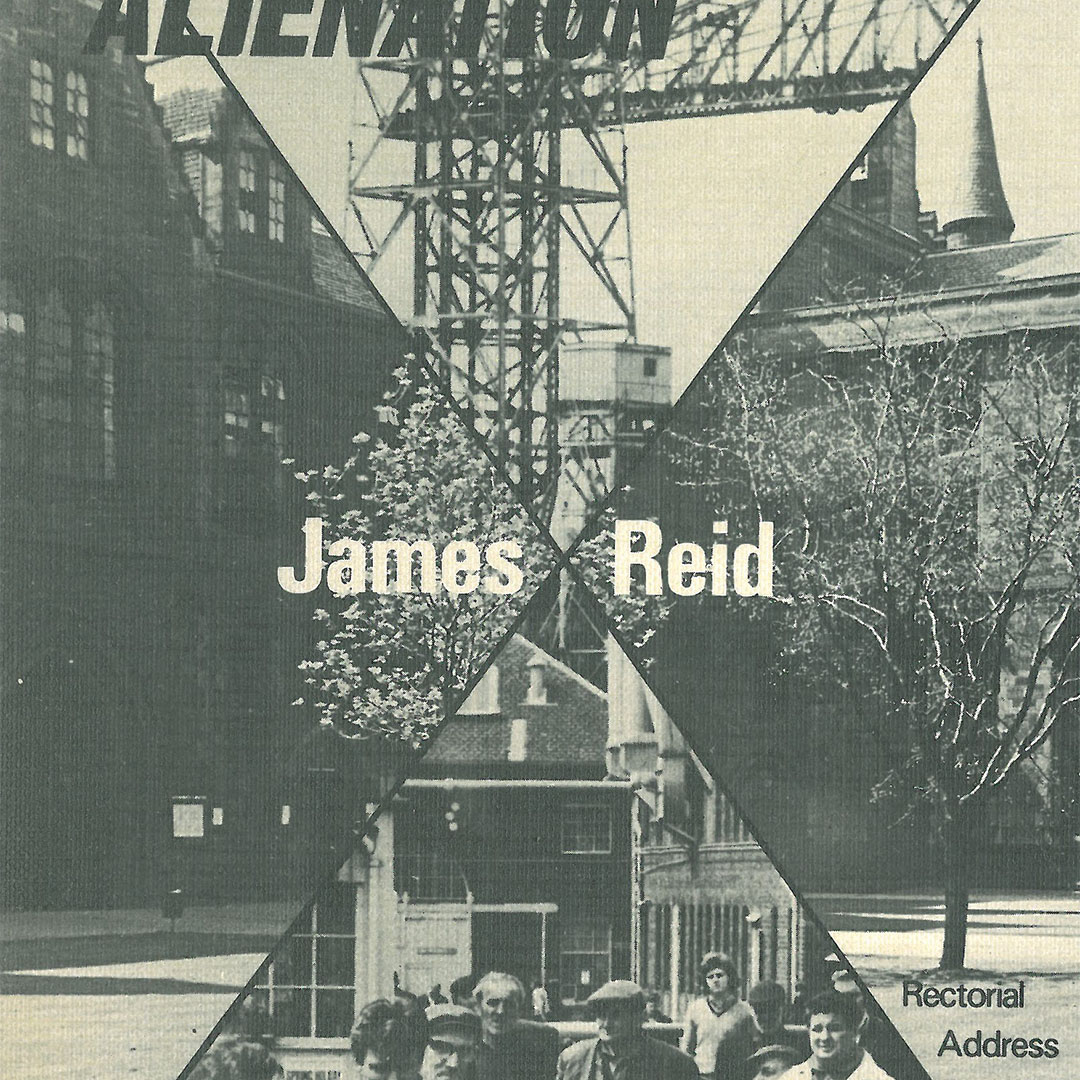

The orator was Jimmy Reid. He was a Glasgow shipyard worker who became a trade unionist, politician, and journalist despite leaving school at 15 with no qualifications.

Jimmy Reid was a Communist – elected on that ticket to Glasgow City Council. In the 70’s that kind of thing still happened especially in the Anglo-Irish communities of Glasgow, Liverpool and Birmingham.

That is enough to scare most Americans stiff, because the perception is so closely intertwined with the horrors of Stalinist Russia and Maoist China.

But Jimmy Reid was a thoughtful, caring man.

Jimmy Reid is probably best described as an ‘anti-capitalist’ and struggled to find a political home throughout his career – being banished from the Great Britain Communist Party for not swearing allegiance to their Moscow and Beijing paymasters, spent time in the Labour Party, and then the Scottish Socialist Party – before finally joining the independence-seeking Scottish Nationalists.

He never won a parliamentary election and is often described as “the greatest MP Scotland never had.”

The speech in question was his oration as the newly nominated Rector of Glasgow University. His election was in part a response by students to his leadership of the Clydeside Shipyard Strikes.

It is a speech which, perhaps, is more relevant to Americans today than when it was so feted and lauded 50 years ago.

If you haven’t read it, here it is Jimmy Reid Speech

He spoke about alienation, or as we in the US refer to it, disenfranchisement.

And his words have, sadly, aged well, seeming more relevant to Americans struggling with the gravest economic, social and environmental challenges for generations.

He talks about those who get left behind by society, are not valued by our elected representatives, and the divergence of what matters to those with power and the priorities of the rest of us.

His speech talks about how alienation “is the cry of men who feel themselves the victims of economic forces beyond their control.”

That will sound mighty relevant to voters in the Rustbelts of Ohio, New Jersey, Philadelphia and upstate-New York, where manufacturing and industrial jobs have disappeared leaving communities decimated and in social ruin.

He speaks of “the feeling of hopelessness and despair that pervades people with justification that they have no real say in shaping or determining their own destinies.”

The anger expressed in America’s communities of colour, by opponents of rampant development changing the nature of the suburban, rural and coastal neighbourhoods we call home, and those fighting the ecological damage to our rivers, oceans, soil and vegetation caused by big business will recognise these frustrations too.

But, perhaps most tellingly, Jimmy Reid talks about how “society and its prevailing sense of values… alienates some from humanity”.

Reid’s oration of 50 years ago is known in shorthand as the “rat race speech” – when the firebrand trade unionist painted the picture of people “scurrying around for position, trampling on others, backstabbing, all in pursuit of personal success.”

Reid explains “it partially dehumanises some people, makes them insensitive, ruthless in their handling of fellow humans, self-centred and grasping.”

And he was ruthless in his portrayal of big business and government’s ‘too cosy’ relationship.

He references “Catch 22”, Joseph Heller’s great American satirical novel, poking fun at the bureaucracy which makes irrational decisions seem rational.

Reid recalls Heller’s description of the book’s character Major Major’s father – “His specialty was alfalfa, and he made a good thing out of not growing any. The government paid him well for not growing any. They paid him well for every bushel of alfalfa he didn’t grow, and the more he didn’t grow, the more money the government gave him, and he spent every penny he didn’t earn on new land to increase the amount of alfalfa he did not produce.”

For Brits smarting about the government’s billion-dollar loss on substandard Personal Protection Equipment acquired from ‘politically-friendly’ contractors, or US residents bewildered by government incompetence such as the decision a-few-years ago to spend multi-millions of dollars on licensing fees for dark green camouflage to drape on our troops heading to the deserts of Afghanistan – this comical critique of the way our governments prioritise and spend our hard-earned tax money will jar.

Again, those struggling to grasp some – any – of the dwindling and finite resources to provide immigration application support, suitable housing, social care, secure jobs, affordable healthcare or funding for education, will recognise themselves as unwilling protagonists in the battle to ‘look after number one’ – or as Reid comically referred to it – ‘Bang the bell, Jack, I’m on the bus”.

But while Reid’s words are as relevant today as they were when he delivered them in Glasgow University’s Bute Hall, it is America’s populist Right who have embraced them for their benefit rather than the radical Left.

It is Trump and his acolytes who now talk about ‘alienation’ and ‘those left behind’.

It was the Brexit-promising Tories who profited from the dissatisfaction of the working classes in the UK’s traditionally socialist industrial and urban North and Midlands, and now the Right, especially the nationalist leaning ones, are using this dissatisfaction not to ‘rise up and demand power for the people’ as Reid urged, but to split and pitch communities against each other in the fight for those resources and opportunities.

On this, the 50th anniversary of this monumental speech, it is worth pondering Reid’s conclusion – “All that is good in man’s heritage involves recognition of our common humanity, an unashamed acknowledgment that man is good by nature.”

As Jimmy said: “To measure social progress by material advancement is not enough. Our aim must be the enrichment of the whole quality of life.” “It’s a goal worth fighting for.”