We like to pretend hospitality just lives in hotels, restaurants, and conference centres.

Yet, we all know, it doesn’t – it lives anywhere a human turns up with expectations, spends money, and hopes not to feel like an afterthought.

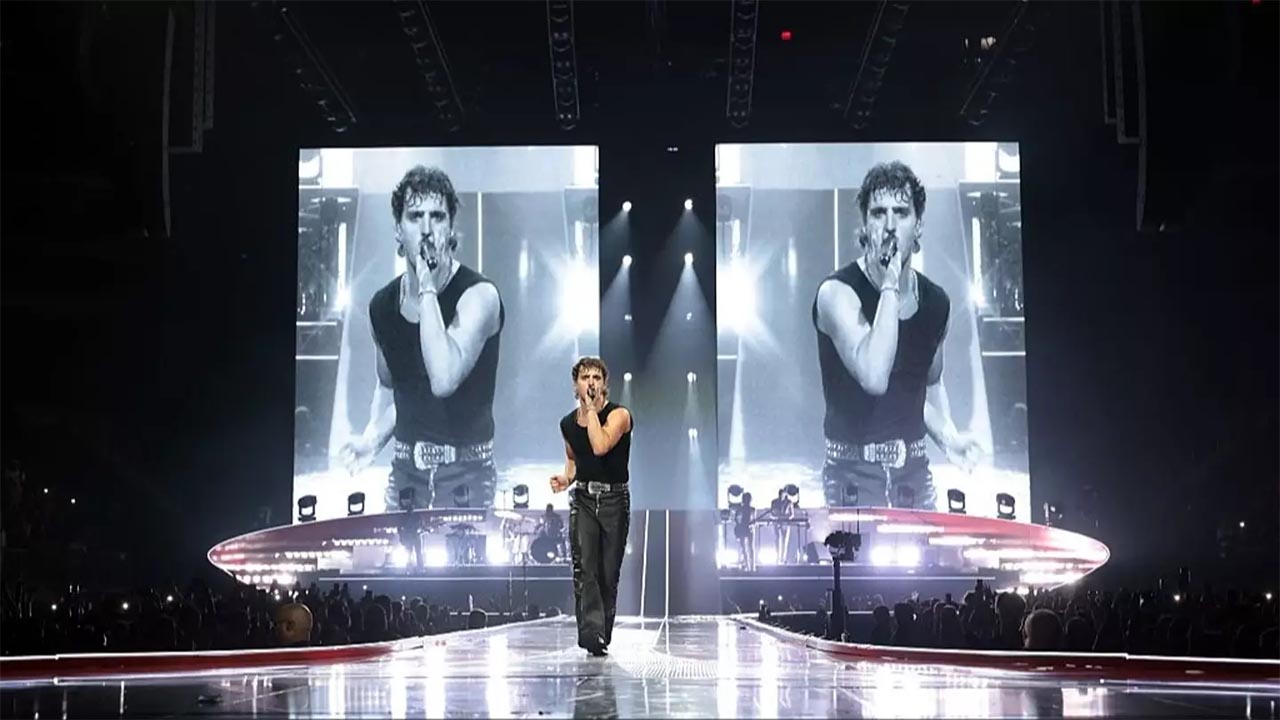

On Monday I went to see Benson Boone at the “newish” Co-Op Arena, Manchester. I’ve been there a few times now.

Experiences have varied, I saw Teddy Swims there once, with a standing only ticket, which was packed to the rafters, a stage at the front, and I then spent the whole night watching the screens because that’s all I could see from the back.

Another time I was seated first tier near the stage edge: faced forward but my view was basically backstage. No screens angled for us, in short, we existed, we paid, but we weren’t really considered. None of that ruined the gigs massively but it always sticks with me.

Then came Benson. This time the stage didn’t sit like a brick at the front; it ran from the front of the stadium, right through to the back of the room. He used every inch of it, up and down, side to side – he even was above the crowd and above the tiered seating through one performance – he got the crowd. There wasn’t a hot heat in the room – the so-called bad seats, didn’t exist. Side blocks got their own screens and angles finally made sense. Every seat became a good seat because the experience was designed on purpose, not left to chance. That’s hospitality in plain clothes: inclusion over assumption, intention over habit.

Translate it into our world and the parallels are obvious. “Every seat must be a good seat” is “every guest must have a good stay.” If the last room left is the smallest, own it, make it the cosy one with the warmest welcome note and a pillow menu that shames the bigger rooms.

Angles and sightlines at a gig are the same as information and access in a venue. If guests keep asking the same question, the information isn’t where it’s needed. Fix the angle. For example, customers are always calling up to know where to park, put that information on your website, on their confirmation email.

Those side seats were a minority, until you count them. Same with dietaries, accessibility, prams, late arrivals. Design for the “rare” and you’ll quietly delight a chunk of your real customer base you’ve been ignoring.

And then there are the micro-moments. A wave to the top tier, a verse on the back platform, a grin to Block H, tiny actions, big loyalty.

In our world that’s carrying bags without being asked, remembering the tonic brand, fixing the wobbly table before they touch it. These moments are cheap; regret is expensive.

If you want something you can do today, do this: walk your venue like a first timer and sit in the worst spot you’ve got, then fix the top three irritations you notice. Put leadership on a visible runway by scheduling floor laps, not hoping they happen.

Here’s the hard truth: most places deliver the product; very few deliver the feeling. The feeling comes from engineering the experience around the customer, especially the ones you usually ignore.

Benson’s team didn’t build a longer stage for fun. They did it to guarantee more people left saying, “I was part of it.” That is the job. We don’t need pyro to do the same. We need intent.

Monday night proved it. A longer stage, smarter screens, and an artist who moved with purpose turned a massive room into a shared moment. Do the same at your place. Make the worst seat a good one. Fix the angles. When people feel considered, they come back, and they bring friends. That’s hospitality, everywhere, every night.